MEGALODON: Hunting the Hunter

By Mark Renz

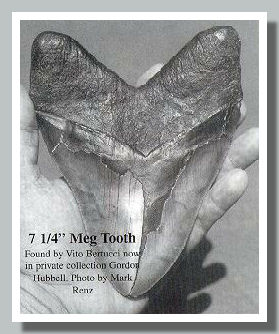

If its massive seven-inch teeth are an indication of size, C. megalodon was one bad shark. Estimates give it 40 to 60 feet between tooth and tail, and a weight of 100,000 pounds on the local fish market scales. Taking VW-size bites out of whales would be no problem for a shark of this proportion.

However, because all we have are a lot of teeth and very few vertebrae, the task of tracing Meg's lineage has not been easy. Today, there is a major rift between researchers, some of whom think this monster-sized shark should be classified as Carcharodon megalodon (which it was called from the early 1800s to 1960), and others who argue that it should be called Carcharocles megalodon, which it was changed to in 1960. Both genus names are in use today.

Meg's closest ancestors, as well as the ancestors of today's great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias), first appear in the fossil record about 60 million years ago, when seas were warm--even at high latitudes. Based on the fossil record, these sharks inhabited the Paleocene seas of southern Russia, Morocco, Angola and the United States. For the professional paleontologist, or even the serious amateur, the phylogenetic map from that point on is riddled with dead-ends and backroads that go anywhere but in a straight line.

Take the final transition of Meg as it was going through the largest stage of tooth development in the early to mid-Miocene. When its teeth were compared with teeth from the great white, scientists assumed the two sharks must be closely related. They saw similarities between the teeth of extremely large great whites and some of Meg's ancestors, such as finer serrations, crown proportions, shape of the root and a broader neck - and classified it as Carchardon megalodon.

Even though mako and great white shark teeth looked a lot alike (with the exception of serrations), researchers passed the similarity off as resulting from the two sharks having similar diets (convergent evolution).

Fossil shark specialist Gordon Hubbell says researchers also previously assumed that the third upper anterior tooth in Meg was positioned in the same manner as great whites, in that the tooth is smaller and has a sharp curve toward the shark's gape. But in studying modern great white shark jaws, as well as associated and partially-associated teeth of Meg and her ancestors, Hubbell reached a different conclusion.

"The third and fourth teeth in megalodons are almost identical in size," he said. "The only difference is that as you go out from the first tooth, it gets slightly smaller and the angle of slant increases very, very slightly. That tells us that because there is no 3rd tooth in there that slants in, or 4th tooth that slants out, there is no space in there where the jaw is constricted."

"The reason why it does that in the white shark is that there is a stricture in the jaw there" added Hubbell. "There is no space for a big tooth to develop. It has to be a little slanted tooth there that angles inward, because the jaw is constricted and there is no pouch in there for it to develop."

According to Hubbell and other researchers, Meg was a dead-end and great whites evolved from makos.

But pro-Carcharodon researchers claim the name should remain unchanged because:

(1) Meg and the great white both have a symmetrical first upper anterior tooth, whereas the mako's first anterior tooth is asymmetrical,

(2) This tooth is the largest in the dentition, whereas the lower second anterior is the largest in makos and other lamndid sharks,

(3) The intermediate teeth point mesially (side of the tooth toward the midline of the jaws where left and right jaws meet) rather than distally (side of the tooth away from the midline of the jaws) as in makos,

(4) The third lower anterior tooth points mesially rather than distally as in makos and other lamndid sharks,

(5) Vertebrae in Megs and great whites more closely resemble each other than with makos.

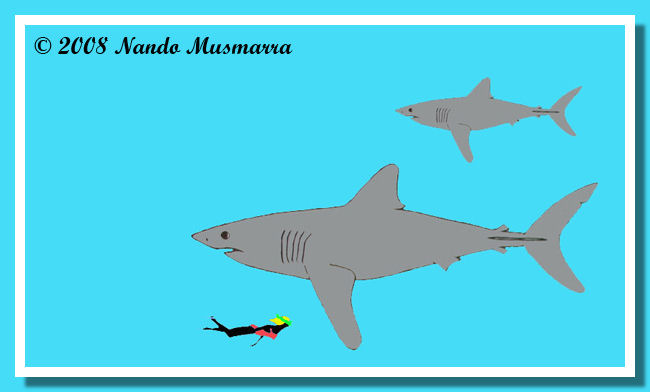

Size comparation between Meg, White shark and man

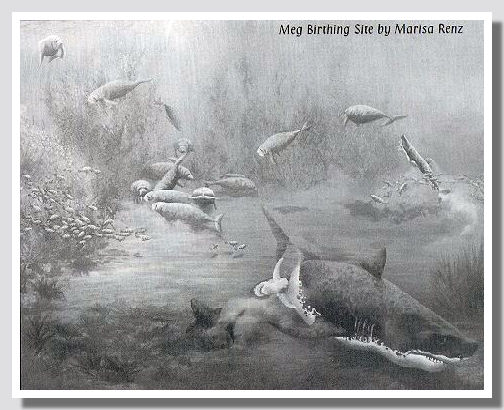

No matter the genus, Meg was the largest predatory fish ever to inhabit our global seas. Adults may have consumed full grown whales while pups may have dined on full-grown 12-foot dugongs.

Meg's demise is also the subject of debate, although most scientists are convinced it's history. The fossil record abruptly ends some two to three million years ago, while rumored sightings extend into the last 100 years. One such "sighting" occurred in 1918. Australian fishermen claimed that a shark the size of a blue whale gulped down their three-foot wide crayfish pots, mooring lines and all.

But shark researcher Gordon Hubbell represents one of many voices in the scientific community who suggests there is no basis for us to get excited about the possibility of a live megalodon somewhere.

"If there was such a creature alive, "says Hubbell, "we would find evidence of it. We would find some kind of a carcass washed up on shore with bite marks on it, or we would see it on sonar screens, or we would see something that would tell us there is something big living down there. It's nice to dream about but it just doesn't exist. And of course, people can say, look at megamouth shark...it was discovered in 1976 off of Hawaii and it's 13 feet long and we didn't know about its existence. But megalodon was a heck of a lot bigger than that. I mean, it was like a small submarine."

If the general consensus among scientists is that Meg is extinct, then what wiped it out? Here are some theories:

1. The Isthmus of Panama rose from the sea three to four million years ago, which possibly blocked the route Megs used for breeding, and may have affected the Gulf Stream and global circulation.

2. Orcas are highly intelligent mammals and may have been in direct competition with Megs for food. Because they were likely craftier than sharks, orcas may have simply out-smarted Megs and gotten to whales and other food sources quicker - leaving less for Meg to eat.

3. Orcas also may have teamed up and attacked lone adult Megs, or selected juvenile Megs as targets to lessen the competition for food. A pod of orcas can number up to 50 individuals. Alone, a 25-foot orca might not stand a chance against a 60-foot Meg, but in a group they could easily have the upper fin.

4. Great white sharks and Megs co-existed for several million years, as evidenced by the recovery of their fossil teeth in the same sediments. But it's unlikely that the adults were in direct competition for food. Instead, they probably divided up the food sources. However, it is possible that the more experienced adult great whites may have dined on inexperienced Meg pups, or that adult great whites may have out-competed juvenile Megs for the same food. If this were the case, then great whites may have been influential - but not solely responsible for -- megalodon's demise.

5. By the end of the Pliocene (1.6 mya), whales were getting quicker, so much so that Megs had a difficult time catching them. Whale musculature and tail structure became refined, while Megs hadn't adjusted to the changes. Some whales began to migrate into colder climates where Meg couldn't survive, while one of meg's likely primary food sources -- an early baleen whale known as a cetotherid -- had become extinct.

Hubbell theorizes that Meg was a specialist, and that when its chief food source was gone, it wasn't long until Meg disappeared too.

"When the whale population disappeared in the tropics and temperate zone, and moved to the Polar regions, Meg couldn't adjust to the the change in diet or change in water temperature," said Hubbell. It got to the point that it was so big and so specialized that it couldn't survive when its main food supply disappeared like that."

According to fossil shark researcher David J. Ward, Meg was overspecialized. "When the climate cooled in the Mid-Pliocene, the food chain disintegrated and Meg became extinct," he says. "Because of their less specialized nature and tolerance to cold water, great whites survived."

Smithsonian shark specialist Robert Purdy has a different opinion. "Large whales are still found in warm waters," he says. "We just don't know (what drove Meg to extinction). There is not much fossil evidence for the history of marine vertebrates for the last three million years."

Where can Meg teeth be found today? Because the shark had global distribution, it's teeth were scattered from Florida, up the eastern seaboard to Maryland, west to California, south to Mexico and South America, and on to Belgium and Japan.

Hunting one of the most ferocious beasts ever to inhabit earth's oceans is not for the timid or inexperienced. Then again, perhaps it is. Bravery, valor and marksmanship may be important for hunting live game, but to pursue a beast as elusive as Meg one needs to rely on a combination of research, persistence and luck.

Oh Meg, where art thou?

© Mark Renz

Mark Renz hunts for Meg teeth in his home state of Florida, where he and his wife Marisa operate a fossil guide service. Signed copies of his book, "MEGALODON: Hunting the Hunter" are available at:

http://www.paleopress.net/index.htm

Si ringraziano Mark e Marisa Renz per il permesso di pubblicare l'articolo e le fotografie

Quest'articolo è stato già pubblicato su Prehistoric Times