The Bürgermeister-Müller Museum (Solnhofen, Germany) and the CARLOS Project

by Nando Musmarra

English translation by Wendell Ricketts

PaleoArt by Loana Riboli

Archaeopteryx family - PaleoArt by Loana Riboli

Archaeopteryx family - PaleoArt by Loana Riboli

The traveler who crosses Bavaria by freeway risks moving much too quickly and missing one of Germany's most enchanting sites: the Altmühl River Valley. Some 150 million years ago, a brackish lagoon once covered the area where romantic villages and world-class taverns now nestle among the hills. Sporadically connected to the Tethys Ocean, the lagoon was dotted with an archipelago of islands (the Vindelicisch Islands) and was largely isolated by a rim of coral reefs..

Most of the fossils found in the Solnhofen Limestone are not those of organisms that lived in the brackish waters of the lagoon but are rather those who inhabited the nearby coral reef, the shallow waters surrounding the islands of the archipelago, or the Tethys Ocean. If this aerobic or anoxic environment was, in one sense, inhospitable and unsuitable for life, in another sense, paradoxically, it offered an ideal death. The brackish lagoon supplied all the requirements necessary for sedimentation to take place and for the organisms that perished there to undergo fossilization. Over time, in short, this prehistoric lagoon was transformed into the kind of ideal exposure in which every paleontology enthusiast dreams of finding himself.

The sedimentary layers deposited in the Altmühl River Valley are today known as the Solnhofen Plattenkalk, a formation of very fine grained Jurassic limestone that is one of the world’s most famous Konservat-Lagerstätten—that is, a deposit characterized both by an unusually rich trove of fossil specimens and by the exceptional state of their conservation. The Solnhofen Plattenkalk is internationally known for the fossils of organisms whose soft parts have also been preserved.

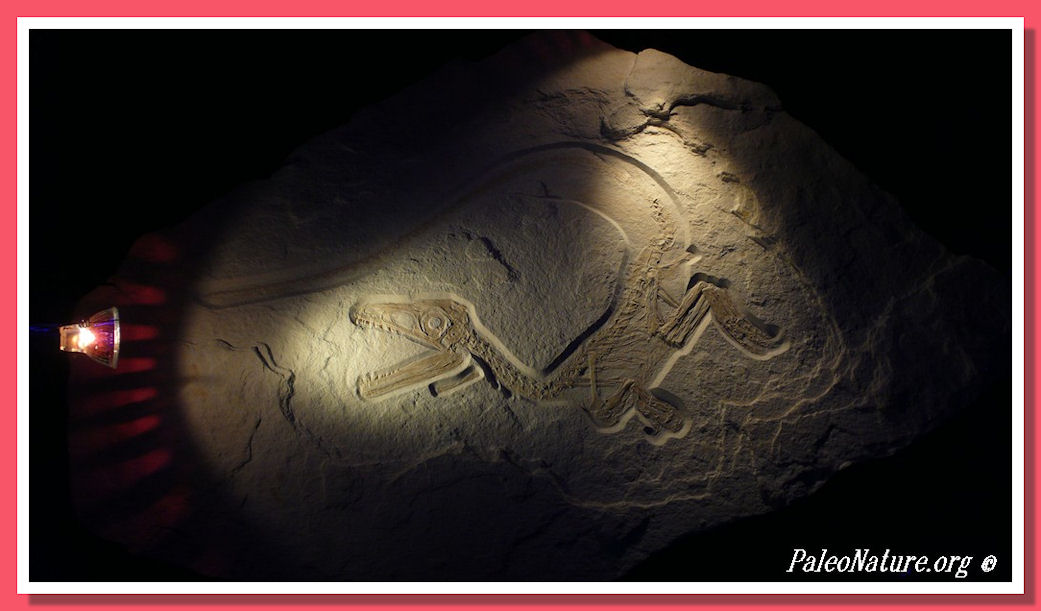

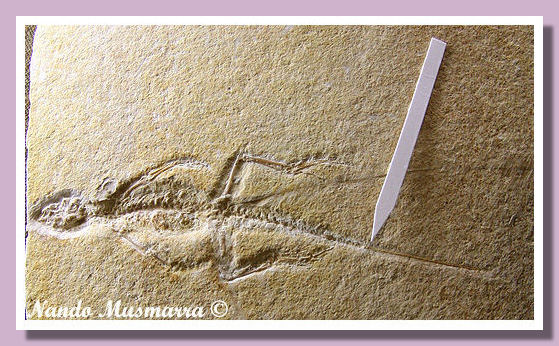

Bellubrunnus rothgaengeri (gen. et sp. nov.). A new Non-Pterodactyloid Pterosaur from the Late Jurassic of Solnhofen

Most of the fossils found in the Solnhofen Limestone are not those of organisms that lived in the brackish waters of the archipelago, but are rather those who inhabited the nearby coral reef and the Tethys Ocean. In all likelihood, they were transported into the lagoon’s still waters by major, violent storms, as were the muddy sediments that covered and protected them during the fossilization process. The result is a fossil fauna that is exceptional both for its diversity and for its extraordinary state of conservation.

The alternating horizontal layers of the Solnhofen deposits make up a characteristic stratigraphic sequence. Yellowish in color, Solnhofen material continues to be extracted on a daily basis for use in building projects. Most of the quarrying and selection is still carried out by hand—in order not to ruin the stone, certainly, but also so as not to miss the chance to examine each slab, one at a time, to make sure that some creature from the late Jurassic (Kimmeridgian/Tithonian) hasn’t left its traces behind in the limestone.

So many species of Mesozoic organisms are found as fossils in the Solnhofen Limestone that to try to list them all here would be impossible. A few, however, can be said to have played a role in the creation of the story of paleontology. To begin with the invertebrates, I am personally fascinated by the echinoderms, which include the extinct crinoids Saccocoma and Pterocoma (floating or free-swimming species that, unlike others of their Class, were not attached to the sea floor by means of a stem); the exquisite and rare starfish Riedaster, Archasteropecten, Lithaster, Pentasteria, Terminaster; and the more common (at least in some quarries) ophiuroids such as Geocoma, Ophiopetra, and Sinosura. But we mustn’t neglect the beautiful Solnhofen echinoids, often found with their spines intact: Hemicidaris, Pedina, Phymopedina, Phymosoma, Plegiocidaris, Polydiadema, Pseudodiadema, Rhabdocidaris, Tetragramma, and Pygurus (the latter is, to date, the only species of regular echinoid known from the Solnhofen Plattenkalk).

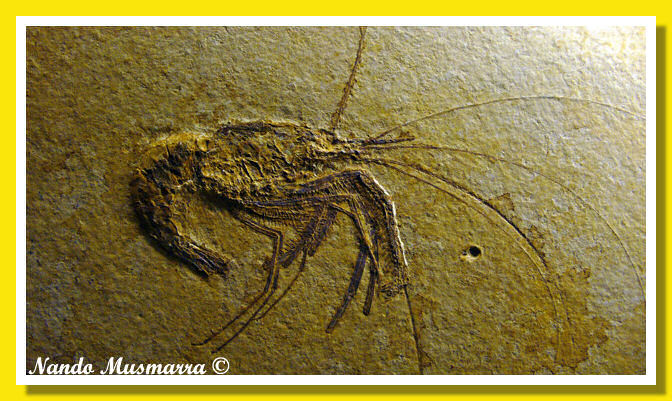

With a greater selection than Seattle’s Pike Place Fish Market, the Museum boasts an especially representative collection of crustaceans: horseshoe crabs (Mesolimulus); barnacles; many species of shrimp; and lobsters, prawns, and other decapods such as Cycleryon, Eryma, Eryon, Knebelia, Magila, Mecochirus, Palaeastacus, Palinurina, Phlyctosoma, and Stenochirus. The delicately detailed fossils of crustacean larvae are a special treat (Phalangites, Palpites, and Phyllosoma), and cephalopods are likewise abundant (belemnites, nautiloids, and ammonites, many of which are preserved with aptychi—a hard anatomical structure like a curved plate, which was part of the body of an ammonite).

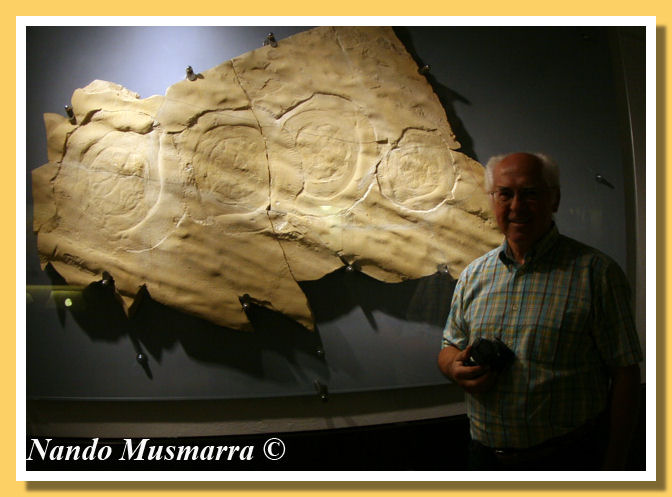

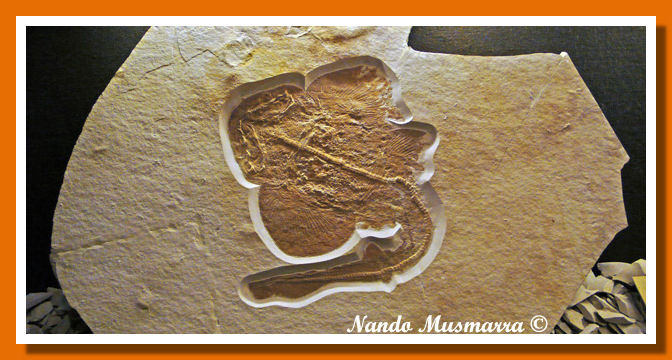

Mollusks find their place here as well, including gastropods and bivalves, while the asymmetrical structures of brachiopods such as Loboidothyris, Terebratula, Lacunosella, and Rhynchonella seem even more evident in these specimens flattened in the Plattenkalk. It is the jellyfish, however (Cannostomites, Epiphyllina, Eulithota, Leptobrachites, and Quadrimedusina, along with the fanastic Rhizostomites and the hydrozoans Acalepha, Acraspedites, Hydrocraspedota , and Medusites), that seem to be the quintessence of the miracle of fossilization. To think that these organisms composed almost entirely of water have come down to us as fossils 150 million years after their deaths defies belief. Sponges, bryozoans, and “flowery” octocorals (it’s interesting to note that the German term for the anthozoa, Blumentiere, literally means “flower animals”) round out the menagerie of the most representative marine invertebrates of the Solnhofen fauna.

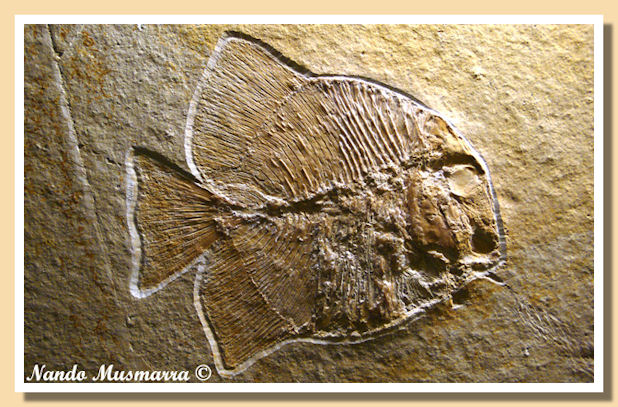

Wolfgang Mages and his four-Rhizostomites slab.

The Bürgermeister-Müller is teeming with fish fossils notable for both their beauty and their diversity. To begin with the cartilaginous species recovered from the Solnhofen Limestone, the Museum’s collection includes exceptional sharks and rays such as Eonotidanodus, Heterodontus, Hybodus, Ischyodus, Macrourogaleus, Orectolobus, Paleocarcharias, Paleoscyllium, Paracestracion, Phorcynis, the enigmatic Protospinax, Aellopos (Spathobatis), Asterodermus, and Pseudorhina.

The Museum’s collection of chimeras such as Chimaeropsis (currently assigned to the cartilaginous fish) deserves a mention as well, as do its specimens of coelacanths such as Coccoderma.

The fossil-bearing strata at Solnhofen have supplied private museums and collections with numerous genera of bony fish, some of which reached gigantic proportions. In the case of many specimens, the fossils are extraordinarily detailed and even more fascinating for the lifelike positions in which these fish are found so long after their deaths. Of the many specimens on display, I was particularly struck by Aspidorhynchus, Belonostomus, Eomesodon, Gyrodus (some of which reached nearly a meter in length), Gyronchus, and Lepidotes.

Rare marine reptiles, such as plesiosaurs and ichthyosaurs, sea turtles (most of which are accounted for within the genus Eurysternum), and crocodiles (Aeolodon, Alligatorellus, Alligatorium, Atoposaurus, Dakosaurus, Geosaurus, and Steneosaurus), round out the description of the vertebrate faunas that once populated the waters of the Solnhofen ocean-lagoon system.

Nor can we neglect the traces and trackways left by organisms on the lagoon bottom, thanks to the absence of deep marine currents. These include many specimens of coprolites, traces of worms, and the trackways of ammonites, horseshoe crabs, shrimp, and other crustaceans. Not infrequently, these tracks and traces are found fossilized together with the creature that made them, a sort of snapshot of the last moments in the life of some unfortunate animal.

Fossil algae are present as well.

The discovery of plant fossils (conifers above all; cycads are less common) alongside those of animals that lived on dry land are evidence that exposed areas of land were nearby. On them, together with innumerable species of insects, sphenodonts lived (Homoeosaurus, Kallimodon, Piocormus, Pleurosaurus), lizards (Eichstaettisaurus, Palaeolacerta), as did small dinosaurs such as Compsognathus (the holotype for the species was actually found at Solnhofen), or the very recent raptors, Juravenator and Sciurumimus/Xaveropterus

The inhabitants of the dry land that emerged in and around what is Solnhofen today included small dinosaurs, about the size of a modern chicken. Perhaps they weren’t sufficiently nourished by the diet available to them, limited as they were to keeping their feet on the ground. Over time, they developed small wings and attempted to challenge the laws of gravity. They would one day become birds, but they didn’t know it yet.

In their clumsy efforts at flight, they did their best to capture the fireflies, mosquitoes, and cicadas that buzzed around them and to share the skies with other, larger winged creatures such as the pterosaurs (Anurognathus, Ctenochasma, Germanodactylus, Gnathosaurus, Pterodactylus, Rhamphorhynchus, and Scaphognathus). But they weren’t yet capable of such a feat: their wings were too small and probably, rather than taking actual flight, they used their rudimentary wings to boost their ability to run and to make longer leaps. That was very likely true of the most famous proto-bird of all, Archaeopteryx.

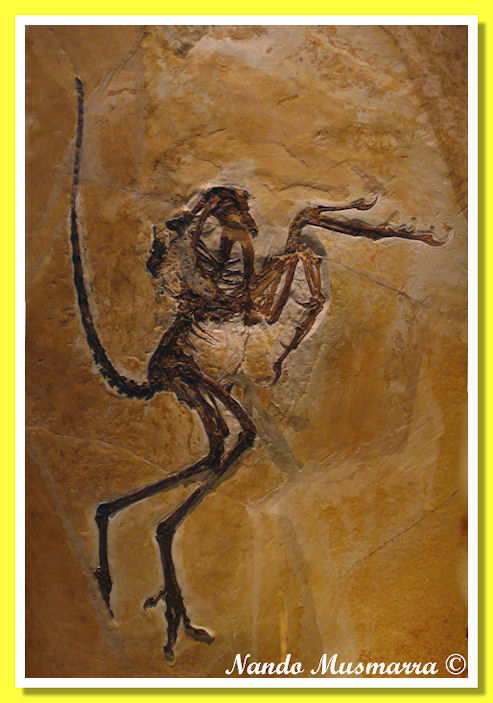

Archaeopteryx , like other primitive birds, combined characteristics belonging to true birds (such as feathers) with those of reptiles (such as tooth morphology and upper limbs outfitted with claws, which became genuine wings in Archaeopteryx). These fascinating fossils have made the Solnhofen Limestone famous the world over, and 2011 marked the 150th anniversary of the discovery of the first Archaeopteryx fossils.

THE SOLNHOFEN MUSEUM

The eleven Archaeopteryx specimens found to date have almost all come from the Plattenkalk quarries located in the twenty kilometers that separate the villages of Eichstätt and Solnhofen. There are three museums open to visitors in this area, each one more fascinating than the last: the Bürgermeister-Müller Museum in Solnhofen, which is the subject of this article, and the Museum Bergér and the Jura-Museum, both in Eichstätt. Up until a few years ago, there was a fourth museum—the Maxberg Museum, which was housed in a series of outbuildings in one of the historic quarries in the village of Mornsheim; unfortunately, the Maxberg closed its doors in 2004.

What fossil-lover hasn’t fantasized, at least once in his life, that he might be lucky enough to discover an Archaeopteryx? And what natural history museum doesn’t dream of being able to display a specimen of this magnificent feathered fossil in its own exhibition halls?

Both dreams have come true for Solnhofen’s Bürgermeister-Müller Museum. Specimen No. 6, which lived alone in the museum’s main hall for many years (although it was occasionally removed for study and a cast displayed in its place), finally has company: Specimen No. 9, known as “Chicken Wing,” discovered in 2004 in a quarry owned by the Ottman & Steil company. For the present, then, the Bürgermeister-Müller Museum is the only institution in the world that can boast of housing two specimens of Archaeopteryx under the same roof (the others are located in London, Berlin, Haarlem, Munich, Eichstätt, Solnhofen, and Thermopolis, Wyoming; Specimen No. 8 (the Daiting specimen) is held in a private collection). Specimen No. 3 (known as the “Maxberg specimen”), is currently out of circulation, but German paleontology buffs continue to hope that, one day soon, the Maxberg Archaeopteryx will be returned to their loving embrace (through they’ll need to keep clear of those claws!). The final resting place for the recently discovered Specimen No. 11 has yet to be determined.

The entrance hall to the Bürgermeister-Müller Museum has been given over to a display of fossils of small reptiles in which tail regrowth is visible, and it is only a prelude to the first exhibition room in which the Museum’s two Archaeopteryx specimens, No. 6 and No. 9, dominate a group of pterodactyls fossilized in every imaginable position.

Another extremely interesting fossil is a magnificent pterodactyl from the Langenaltheim Quarry, the cranium of which exhibits portions of fossilized soft tissue. For the time being, this specimen, which is quite similar to Pterodactylus antiquus but differs in its tibial-femoral proportions, has been cautiously identified as Pterodactylus sp. Masterfully prepped under ultraviolet light, this invaluable fossil is also the first pterodactyl specimen to demonstrate with certainty that these splendid flying reptiles possessed a beak composed of keratin.

Down a hallway whose “furnishings” include a specimen of Geosaurus (an enormous crocodile), an ichthyosaur, and a small plesiosaur, the visitor arrives in a second exhibition hall where a grand mass-mortality plate, covered with the fossils of a vast number of small fish, is on display.

The third hall is a genuine fossil aquarium dedicated to the Chondrichthyes or cartilaginous fish. Here, the Museum’s collections include remarkable specimens of such shark and ray species as Paleocarcharisas,Phorcynis,Heterodontus,Orectolobus,Pseudorhina, and Squatina.

Beyond a passageway lined by two large slabs bearing the positive and negative impressions of an enormous ammonite, the first of the exhibition rooms dedicated to the invertebrates awaits. These displays nearly give the impression of having been placed off to one side, almost as if the Museum felt inclined to protect its true treasures from invasion by groups of noisy school children. This is the area of the Museum that impressed me the most. Here, jellyfish, hydrozoans (the so-called Hydromedusae), crinoids, sea urchins, and starfish show the way to other exhibition rooms in which countless species of crustaceans are on display, all of them important both for their beauty and their scientific value. Beyond that lie a display of insect fossils; another of the traces left on the sea floor by horseshoe crabs, shrimp, and lobsters; and yet another of fish coprolites in both braided and oval shapes—including one that shows an unmistakable assemblage of spines, the evidence of the mid-day meal of some finned epicure of long ago, one that preferred sea urchins to other ocean delicacies.

Another exhibition room is dedicated entirely to fish. The magnificent specimens of Aspidorhynchus and giant Gyrodus displayed here are almost always “doubles,” which is to say that both a “positive” and “negative” fossil (or “part” and “counterpart,” to use slightly more technical terms) of the animal are exposed in the stone slabs. Another hallway, decorated with large fish specimens that couldn’t be fitted into the previous room, leads to display cases containing specimens of Sarcopterygii (Coccoderma, Holophagus, Libys, and Macropoma). Finally, a stairway shows the way to the brightly lit top floor, which until recently was entirely dedicated to the history of lithography.

THE INVENTION OF LITHOGRAPHY

The quarrying of Solnhofen Limestone has gone on for centuries. The thicker, more resistant layers have traditionally been used as paving or even building stones, while thinner slabs, used in the past as roofing materials, have found new life as home and office décor because of the highly prized manganese oxide dendrites found in them.

The Solnhofen Limestone was immortalized in 1798 by Alois Senefelder, the inventor of the technique of lithography. Senefelder polished the homogenous, tightly compact blocks of Solnhofen limestone and drew on their surfaces with oil-based wax crayon. The limestone plate was then inked and dampened. Sheets of paper placed over the plate and passed through a press emerged with the imprint of only those parts of the image that had been drawn with the wax crayon (to which the ink adhered). Prints were a mirror image of the original design and a single matrix was sufficient to create an unlimited number of copies. Perhaps Senefelder was even inspired to create the lithographic print technique after seeing a slab of flattened Solnhofen fossils.

THE CARLOS PROJECT AND THE EVOLUTION OF THE MEDITERRANEAN SEA

The Bürgermeister-Müller Museum was founded some forty years ago as a project of then-mayor Friedrich Müller, a paleontology buff who wanted a museum to serve as a permanent home for his own magnificent collection of fossils from the area. Even today, Solnhofen’s residents (Solnhofenheimers?) remain proud that their museum is dedicated exclusively to local paleontology and collecting.

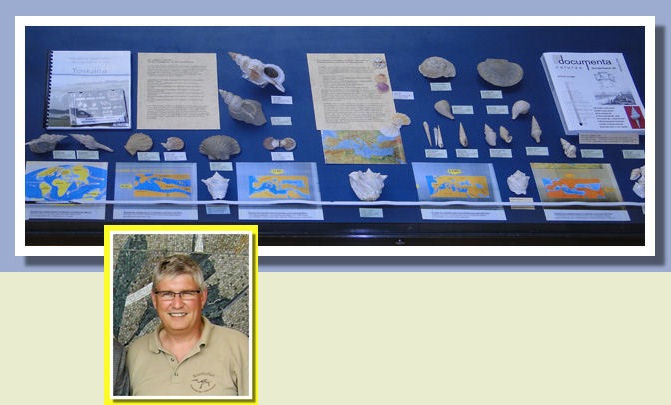

Over the years, however, the Museum’s collection of Plio-Pleistocene fossil shells of the Mediterranean, the Red Sea, and Florida has continued to grow and now spreads throughout the museum’s third floor.

This exhibit is the result of the great affection the director and volunteers of the Bürgermeister-Müller Museum feel for Italy and the Mediterranean Sea. In fact, that affection has taken concrete form in the establishment of the “CARLOS Project,” an initiative whose goal is to open a permanent center in the Bürgermeister-Müller Museum for the research and study of fossil and living mollusks from the Mediterranean area and of the climatic and geological events that have taken place in and around the Mediterranean over the last tens of millions of years.

The group that conceived and has organized the CARLOS Project is composed of enthusiastic amateurs and professionals in paleontology and malacology from Italy and Germany. The project’s science officer is Dr. Martin Röper, director of the Bürgermeister-Müller Museum.

Photo courtesy of Wolfgang Mages ©

At the beginning of 2011, the first phase of the project was presented to the public. An exposition entitled Fossil Mollusks included a display of the fossil shells of animals that had lived in the Mediterranean area over the last five million years. The exhibit compared Mediterranean molluscan faunas with those of Florida’s Caloosahatchee Formation and of the Egyptian Pleistocene.

The goal of the CARLOS Project is to use the display of fossil molluscan faunas as a tool to represent the evolution of the Mediterranean Sea from the end of the Cretaceous to the present, beginning with the closure toward the east of the vast Tethys Ocean, which once included what is now the Mediterranean. The result of the collision of the Indian and African Plates with the Eurasian Plate, in addition to giving birth to the Alps and the Himalayas, was the separation of the Tethys and Indian Oceans and the subsequent division of their faunal populations in two.

To the west, connections to the North Atlantic were also closed, and the large Gulf of Tethys continued to be inhabited by reef-building organisms typical of tropical environments.

This great body of water, trapped between Europe and Africa, was divided into two large areas: to the northeast was the Paratethys or Sarmatian Sea (represented today by the Caspian Sea, the Aral Sea, and the Black Sea); farther to the southeast lay the Mediterranean Sea whose contours were substantially identical to what they are today.

Photo courtesy of Wolfgang Mages ©

The Mediterranean, in fact, isolated as it was from the open ocean for more than ten million years, was transformed into something very similar to a vast salt lake. The limited variety of organisms present in this circumscribed sea was already sufficient to create a critical situation for its fauna, but the so-called Messinian Salinity Crisis delivered a further blow: high average temperatures led to elevated levels of evaporation, recirculation or turnover of water was non-existent, and the introduction of river or stream runoffs was at an absolute minimum.

Under normal conditions, an isolated sea, even one as large as the Mediterranean, would have its days numbered—somewhat like what is occurring today in the euxinic Black Sea basin (in geology and hydrology, the word “euxinic” indicates water conditions without recirculation and in which oxygen is largely or entirely absent; the term derives from the Latin name for the Black Sea, Pontus Euxinus). According to geologists, in fact, the future of the Black Sea is even darker than its name suggests.

Photo courtesy of Wolfgang Mages ©

Like the mythical phoenix, however, the Mediterranean managed to find a new existence, aided by the geological and climatic events that took place in Europe during the Plio-Pleistocene. Among these were the reopening of the Strait of Gibraltar (and the penetration into the environment of new faunas from the North Atlantic), significant tectonic activity, major volcanism (which brought the birth of new island groups) and, in particular, a general cooling of temperatures, a phenomenon that began in the Early Pliocene (Zanclean) and continued until the Pleistocene glaciation, interrupted only by a relatively warm period that took place during the Late Pliocene (the Piacenzian). As a result of these events, a new source of water became available to the Mediterranean, one large enough to permit repopulation by new faunas and, ultimately, the establishment of improved, more stable biological and environmental conditions that provided the oxygenation necessary to allow these new faunas to survive.

Drainage from the immense glaciers that melted during interglacial periods, along with the still more recent immigrations of new faunas from the Red Sea following the opening of the Suez Canal, are the final events in this brief overview of the history of the “Mare Nostrum,” the Mediterranean, that grand body of water that stretches between the Pillars of Hercules and the system of “straits” represented by the Dardanelles and the Bosporus. The Mediterranean has survived to the present day and, assuming that no catastrophe takes place, will likely endure until the movement of the African Plate, as it continues to press against the Europe and the Eurasian Plates, signals its final disappearance.

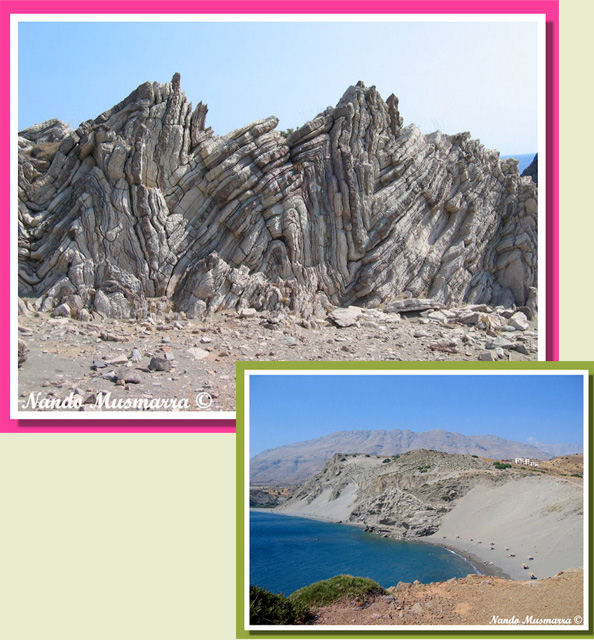

Folded Rocks in Crete

The author is grateful to Wolfgang Mages for the photographs that accompany this article.

Many thanks to Dr. Martin Röper, director of the Bürgermeister-Müller Museum for kindness, open doors, and info.

Nando Musmarra ©