The Dunrobba Fossil Forest

A jewel in Umbria, Italy where the wood even burns!

by Diana Fattori and Nando Musmarra

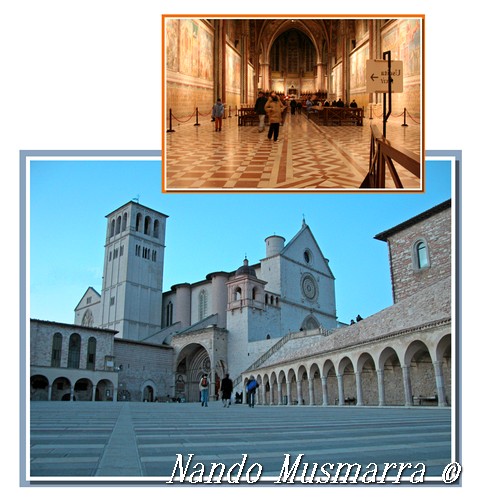

Small, far from the Mediterranean sea, the Umbria region is the geographic center of Italy. Its human occupation started more than 4000 years B.C., when Neolithic cultures devoted to agriculture lived in the region. Centuries later, Umbria became the land of the Etruscans— inscriptions both in Latin and Etruscan are dated back to the second century B.C.—then the Romans came, and when the Empire fell, the Middle Ages commenced. One of the most notable Umbrian characters from that period is St. Francis of Assisi, the man who extended compassion and love to nature in its totality. Today the most visited monument in Assisi is the St. Francis Basilica, lavishly decorated by some of the best 13th and 14th century Italian painters— Cimabue, Giotto, Simone Martini and Pietro Lorenzetti.

Assisi Basilica, UNESCO World Heritage site

Last September Nando and I were looking for a nature full immersion vacation not far from home. We decided to skip the overpriced Tuscany, so we left Rome on a nice fall morning and drove north to Gubbio, Umbria, to reach the place where in 1980 Walter Alvarez and Luis Alvarez discovered and identified for the first time the iridium-rich sediment marking the Cretaceous-Tertiary (K-T) boundary.

Halfway between Rome and Gubbio there is one of the best-kept secrets in Umbria, the Dunarobba fossil forest, point of special interest near the small town of Avigliano Umbro. We left the freeway and followed the brown signs to Dunarobba, where our friends Angela and Federico offered to guide us through the site.Both geologists, Angela is associate professor and Quaternary geology researcher at the University of Perugia, while Federico is a freelance geologist and member of the Umbria Mineral and Fossil Club (GUMP).

.

Angela Baldanza smiling in the mummified forest

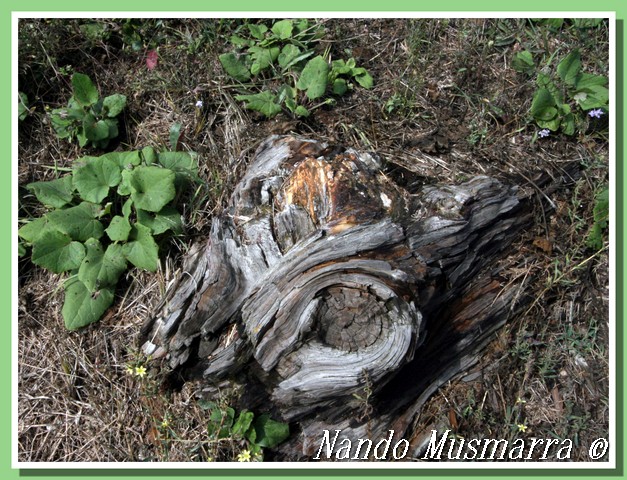

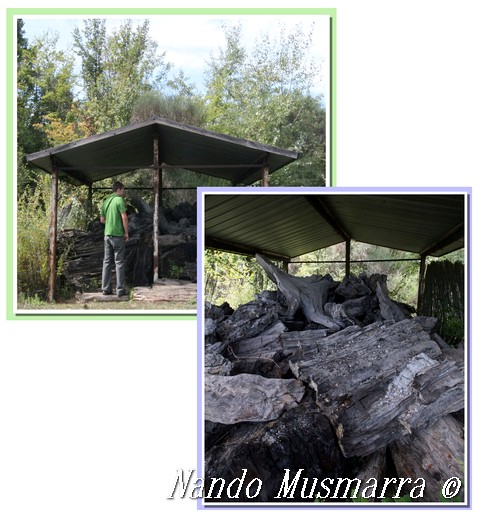

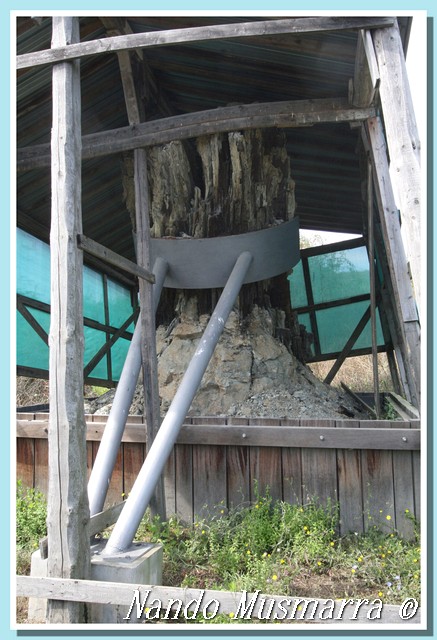

Following the easy trail we reached the gate from where we enjoyed the fossil forest overlook. Walking down the hill, we came into the small valley and finally we went closer to the fossil trees, covered by protective huts. The fossil forest is composed of more than 50 specimens. Each of them is oriented 25 degrees to the east as a consequence of the geological dipping of the rock containing the trees. The forest was formed on the edge of what was an intermountain basement. The fossil remains are testimony of the Pliocene-Pleistocene deposits of the Tiberino Lake Basin.

Federico Famiani checking wood preservation

From Carboniferous to Pleistocene, petrified trees are not a novelty in geological records, but the Dunarobba forest is special because every tree is in life position. Also if formed during latest Pliocene to early Pleistocene, 2.5 million years ago, the trees show an unusual fossilization: totally insulated by clay, the trunks were preserved and they are not petrified but mummified. In the whole world just three more fossil forest locations have preserved mummified wood in upright position: the fossil forest of Axel Heiberg, Queen Elizabeth Islands, Nunavut (Arctic region of Canada), the fossil forest in the Rhein river valley near Bonn, Germany, and one in the Bukkabrany region, Hungary, freshly discovered in 2007. As many of you know, it is easier to identify fossil leaves than fossil wood. Leaves are compared by shape; wood needs more accurate studies. After several palynological and dendrochronological analyses, the Dunarobba trees were referred to the extinct cypress Glyptostrobus sp., very similar to the endangered conifer Glyptostrobus pensilis (Chinese swamp cypress) still living in swamps and along stream banks in a few select areas of China and Vietnam. Associated with the stumps are also fossil remains of fruits— small cones about the size of a dime—and leaves in the shape of small linear needles.

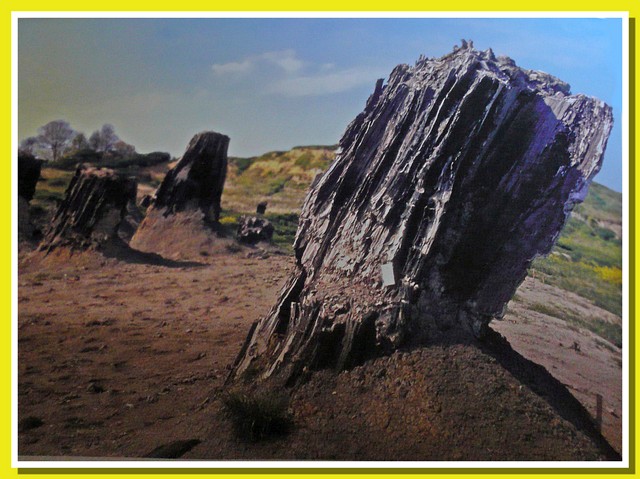

Dunarobba fossil forest in the early 80’s

The Dunarobba forest discovery is dated back to 1620, when the Prince Federico Cesi, founder of the prestigious institute Accademia dei Lincei in Rome, started the study of those fossil trees. Ten years later, in 1630, his colleague Francesco Stelluti continued the study. At that time, the Accademia dei Lincei research method basically involved making drawings of all objects which were studied, so most of the studies on the trees done by Cesi and Stelluti were not written papers but drawings of more than 200 stump specimens. One hundred years later, the King of England, George III, bought the drawing collection, now housed in Windsor Castle Royal Library in London. In those “prehistoric” paleontological studies, the unusual stumps were called “metallofites,” and were thought to be sort of fancy natural features, half plants and half metals.

Dunarobba fossil forest in the early 80's

After that, for a very long time no one was interested in the topic, and scientists forgot the forest for three long centuries. Finally, in 1980, Claudio Sensi, amateur paleontologist and president of the Umbria Mineral and Fossil Club, went to Dunarobba to inspect the trees. At that time, where now there is the open air museum, there was a clay quarry. The quarry workers knew about unusual trees deeply embedded into the clay, and informed Claudio. As he cleared away the dirt from the first stump, he immediately realized that something really interesting was hidden under several feet of clay. Claudio contacted the Perugia University and from then on, professional scientists started accurate studies on the fossil trees.

Claudio Sensi, the Dunarobba Fossil Forest's rediscoverer

Because the trees are mummified, the Dunarobba forest is a fragile site—the stumps could still be attacked by fire and insects. The Florence Wood Research Institute was recently asked to help the trees. Usually the Institute takes care of very ancient paintings using special products to preserve and restore frames and painting supports from the many problems caused by time, weather exposure and parasites. One of the deadliest problems of the Dunarobba trees is caused by Xilocopha violacea, a colorful bee that drills holes in the still-soft wood to feed on cellulose.

Burrow trails left by Xilocopha violacea

For the first time, the restoration specialists were asked to fix 2.5-million-year-old mummified wood! Around some of the trees was built a glass and steel climatized room in order to keep the mummified fossils at low temperature. The specialists also coated the stumps with special resins both transpirant and transparent, so visitors can clearly see the wood structure and the preservation is guaranteed.

Inside the fossil forest no vertebrate remains were found—just fresh-water and brackish fossil invertebrate like small gastropods, ostracods, decapods and lamellibranchs. Those fossils indicate a warmer climate compared to the present day’s.

Next to the visitors’ information building there are the Paleobotanic Center—exhibiting several fossil mammals found at paleosites not far from the fossil forest—and the Arboretum, a reconstructed Dunarobba forest with modern day plants including species from the fossil forest.

Although the wood is not colorful like that at the Arizona Petrified Forest, the one in Dunarobba is really an unusual place, with the extra bonus to be included in one of the most beautiful regions of Italy. The food is also excellent, the people very nice… we were totally hooked by the forest and our time flew very fast. The sunset came and the four of us were still talking about the rare mummified wood. So what about the K-T boundary? Maybe next time…

Decorative plates for sale at Visitor’s center

References

A. Barili, G. Basilici, Z. Cerquaglia, S. Vergoni, 2008.

Foresta Fossile di Dunarobba, Ediart.

Various Authors, 2000. La Foresta Fossile di Dunarobba,

Contesto Geologico e Sedimentario, la Conservazione e

la Fruizione, Ediart.

A. Baldanza, G. Sabatino, M. Triscari, M. C. De Angelis,

2009. The Dunarobba Fossil Forest (Umbria, Italy):

mineralogical transformations evidences as possible

decay effects, An International Journal of MINERALOGY,

CRYSTALLOGRAPHY, GEOCHEMISTRY, ORE

DEPOSITS, PETROLOGY, VOLCANOLOGY, Per. Mineral. 78

(3): 51-60.

Diana Fattori © 2009

This article was published on Fossil News Volume 16, Number 5 — May, 2010